Through grief, restlessness, tragedy and triumph, food has been a central thread for Valentine Warner. Rosalind Sack meets the cook, food writer and broadcaster to ponder the enduring lure of the kitchen.

We all, if we’re lucky, have a place in our homes that soothes the soul in times of turbulence. A place to take comfort, to distract or to quietly contemplate. Where we can be, and often embark on a ritual of doing, that makes us feel better. It could be easing into a deep stretch on a wrinkled yoga mat in a sunny living room corner, or rhythmically digging the garden’s heavy soil. It might be sliding your head under the bubbly bath water into a brief, muffled moment of calm.

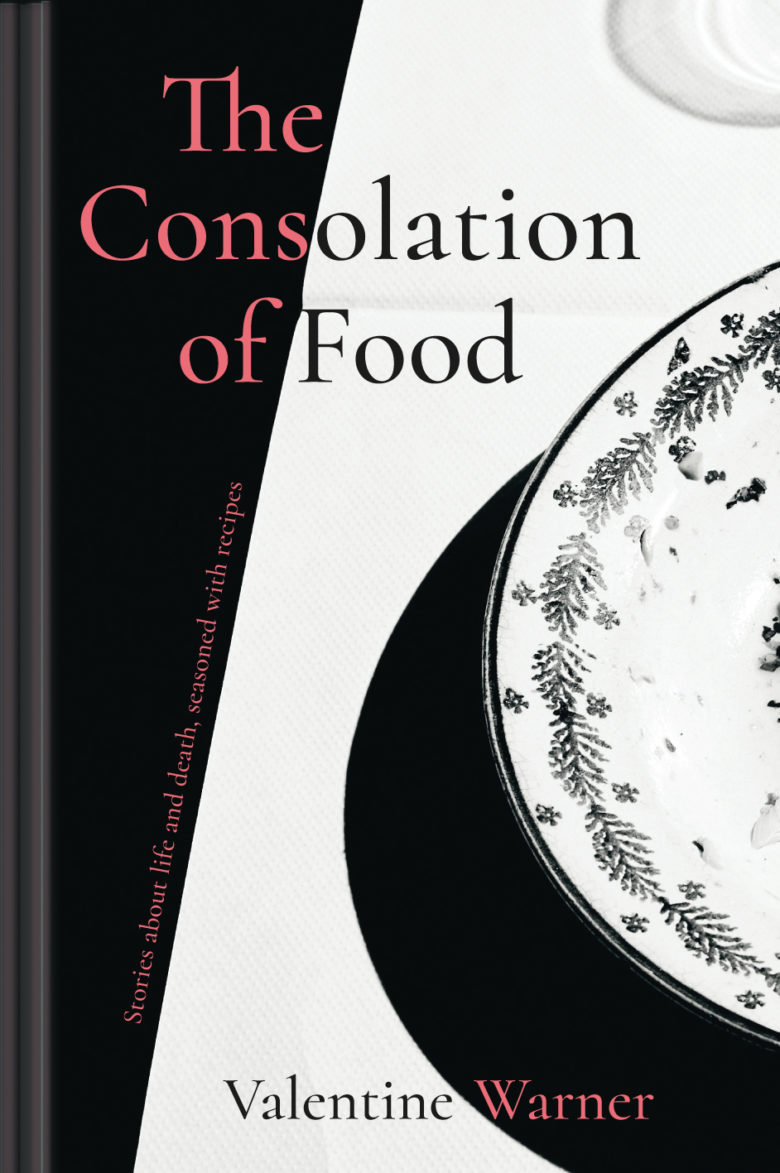

It is perhaps unsurprising that it’s in the act of cooking and preparing food in his kitchen that Valentine Warner finds that much-needed release – as referenced in the title of his touching, mischievous and dryly humorous new book, The Consolation of Food.

“If I can’t solve a problem, if I have a deadline that I might even have missed, if there’s something that I can’t face dealing with and I have to close off and think my way through, then I automatically find myself cooking,” he says. “Cooking is my alphabet, it’s my currency, it’s my second nature. I don’t think when I’m doing it, I’m acting on hunches, I’m acting on absolute knowledge of what I’m working with and it’s a total release.”

Val describes his kitchen in his London home as “very, very personal,” with matte stainless-steel IKEA units, thick wooden worktops, a deep butler sink, a yolk yellow floor and a La Cornue oven that resembles a small tank. There, as in most kitchens, he has a self-confessed propensity to set tea towels on fire.

“In my kitchen I’m surrounded by the things I love,” he enthuses, “I have Alan Davidson’s fish kettle, little sake mugs from Japan, all the bits I’ve collected [on my travels] and, of course, my knives and old pans that I’ve dragged around for years. I love plates, so I have an old dinner service of my parents and a beautiful bowl I’ve found in a shop somewhere.” His love of nature’s larder, of fishing and hunting, means that Val’s home kitchen also needs to be practical: “If you can’t fit a turbot in the sink then it’s the wrong sized sink,” he explains. “I could never have a normal sized oven because, who knows, I might put half a goat into it. Things are a bit more outsized.”

One of Val’s most prized possessions, hung in the kitchen, is a large artwork by the artist Eduardo Paolozzi, who was great friends with his mother. “It has bombs and bodies and spines and hidden faces and tessellating patterns, it’s really nuts. If you want to understand the mayhem of my brain, that picture is it. I love it,” says Val who, himself, trained as a portrait painter.

A book of comfort food, in the truest sense of the word, The Consolation of Food is about the affirmative powers of cooking and eating. In Val’s case, while enduring a divorce and the pain of a long-distance relationship with his children who live abroad with their mum, and grieving the loss of his father, Sir Frederick Warner, a former diplomat. It’s a beautifully-written story book seasoned with recipes. “I spent a lot of time walking away from the writing because I had knots in my stomach. So I’d go downstairs and cook something,” he says.

While our homes can have the power to heal, they can also be a stark reminder of difficult times. And when the house where the choreography of family life once flowed with ease is no longer your home, it can be a tough adjustment.

Val recalls moving into his girlfriend’s studio flat during his divorce: “My girlfriend was amazing to share such a tiny space with such a tall, expansive, restless man. But it was a constant reminder, in a funny kind of way, of the difficulty I was going through.”

Followers of Val’s may already be familiar with his regular ‘Kitchen Beets’ playlists of music for cooking (and eating) to and his book also includes his ‘Radio Val’ recommended listening list. On music, he writes: “I keep it for sulking, driving (except when trying to park), easy Sundays and dancing in the kitchen. Later at night, it is a favourite pastime to climb on my sturdy marble table (podium) wearing my earphones and boxer shorts, and bop until 1am. Instantly preferable to exercising in that most wretched of places, the gym.”

Music has always been central to Val: “My mum’s a brilliant jazz singer, my sister has one of the greatest collections of vinyl I’ve ever seen and my dad would be seen weeping in operas. Music has been very, very important in my family because it’s always been on.”

Growing up in a food-obsessed family on a farm in Dorset, theirs was a big farmhouse kitchen with an oil-guzzling Aga, with meals enjoyed by the window overlooking the garden. “Meals were always looked forward to – you’d finish one and wait for the next,” he recalls. “My brother and I went to collect milk every night and no doubt dropped Lego into the milk tank every night, and Dad was always making rosehip cough mixture or showing us piles of Shaggy Inkcaps. There was a kitchen garden which we raided senseless – it used to drive my mother mad,” he chuckles.

When Val wasn’t at boarding school in Hampshire, he embraced farm life: “It totally fitted who I was as a kid; everything fascinated me and I could go off and break things, or play with things, or build a camp, or fish… And I became interested in nature because food is nature brought indoors. I started to view the world as edible and inedible.”

Hugely sociable, his parents would entertain a constant stream of impressive people at their home: “As a seven-year-old, sitting next to Harold Pinter meant little to me then – if only I’d paid more attention, as I’d love to talk to him now. There was food, lots of food, and amazing people being very expansive and talking and arguing. Food always seemed to raise the volume in the house. It was very gestural, it was showing people that you loved them and wanted them to have a good time.”

Yet, while the more complex and theatrical food was seemingly never in short supply, it’s the humble dishes that are pivotal in Val’s most enduring memories. “If I ever take a tin of sardines out of the cupboard it makes me think of Mum. We’d be watching television and she would quickly mash up some with ketchup and put some Worcester sauce in it and capers and chop up some parsley and then spread it on toast and we’d have it on our knees on a little napkin. Mum was a genius. She never cooked me a bad meal, but they weren’t just good, they were delicious, because of that bit of lemon rind she’d put in, or that touch of curry powder,” recalls Val.

“Scrambled eggs make me think of my Dad. Always. He had rules; cook it slowly, stir it slowly, only butter never milk. They should be wet and oozy and spread across the plate. And if they’re on a slice of toast that’s burnt slightly it reminds me of him even more; he’d burn his toast on purpose because he liked the charcoal taste.”

Val describes his book as a kind of farewell to his father: “I think I spent a lot of time trying to be like my dad, so it was very nice to let that go,” he says, explaining that, even 24 years after his death, his father frequently visits. “I will look up and find myself staring at a cupboard door, or at the kitchen sink and that’s where he is in the room. I’m a great believer in magic and a very spiritual world.”

Now, Val’s relationship with home is tinged with an element of conflict: “My home is in London but I don’t know if London is really where I want to be any more… I love the city, I love art galleries, but I never pine for them. But keep me out of the countryside, keep me out of the trees and off the water and in the concrete for too long and I pine for it.”

With a private catering company based in London, a gin distillery in the moorlands of Northumberland, a restaurant and hotel business in Norway’s rugged Lofoten islands and his children living in the Pyrenees, he says: “I wish I knew what home was more, actually. What I do know is that when I have my children with me then I don’t need a home, then I feel complete.”

The Consolation of Food by Valentine Warner, published by Pavilion Books, RRP £20, is available now.

We were lucky enough for Val to visit The Talbot, Malton in February for a lovely evening of food, drinks and readings from this hugely enjoyable new book.

📍 Bookmark for your next Cotswolds visit!

A guide to Castle Combe 🌿

Often rated as the “prettiest village in England,” Castle Combe is a delightful destination in the Cotswolds.

Here’s a weekend guide to help you make the most of your visit:

* Explore Castle Combe Village

* Wander through the charming streets and admire the historic buildings that haven’t changed since the 15th century.

* Visit the medieval Market Cross, which sits at the heart of the village. It’s a reminder of when Castle Combe was granted the right to hold a weekly market in 1440.

* Take a 60-minute Step Back in Time village tour with a costumed guide to learn more about the village’s history

* The Manor House Hotel was once a manor house built in the valley below the castle ruins. It’s now a beautiful hotel and a luxurious escape for a weekend.

* Motorsport enthusiasts can visit the Castle Combe Circuit, the South West’s premier racing venue. Enjoy race meetings, car shows, and driving experiences.

* Take a leisurely stroll along the By Brook, which flows through the village. Enjoy the peaceful surroundings and picturesque views.

* Visit lovely St Andrew’s Church, known for its medieval architecture and serene atmosphere.

* Cotswold Water Park - If you have extra time, explore the nearby Cotswold Water Park, which offers lakes, walking trails, and water-based fun!

Enjoy exploring and remember to savour the tranquility and charm of this beautiful Cotswolds gem! #CountryCreatures

Sun is shining and we are making the most of it at our @doubleredduke this morning! #CountryCreatures

Last month we welcomed @chefcalum to our @doubleredduke for the first of our 2024 #CountryCreaturesChefSeries

The Pie King did not disappoint! Delivering on his promise of giant Beef Wellingtons, which delighted our Duke guests and impressed our chefs!

Thank you to Calum and everyone who joined us! More brilliant guest chefs coming soon… #DoubleRedDuke

Perfectly pruned hedgerows and cosy Cotswolds cottages! Beautifully captured by the wonderful @sparrowinlondon 🌿

What better way to prepare for England`s quarter final clash than a fire-side feast at our @doubleredduke before cheering on the boys with our giant screen in the pub! 🏆 #CountryCreatures